Citing Buddhist Scriptures: A Guide for Scholars and Practitioners

Citing Buddhist scripture can be somewhat confusing at times. This blog post aims to provide a clear and concise guide to the most commonly used citation styles by Buddhist scholars.

I hope this information will be especially useful for those who wish to use Buddhist scripture in their research or writing.

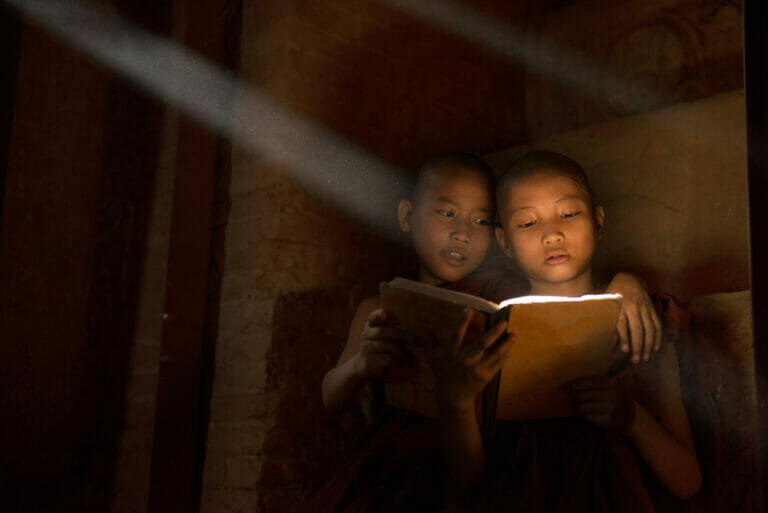

The scriptures of Buddhism are the texts that provide the foundation of Buddhist philosophy.

These texts include all the core teachings, including those on ethics, karma, and meditation. As part of the Buddhist tradition, scriptures are both revered and studied extensively.

Citation is a way to attribute information presented in another writer’s work. You should cite both where you found the information (usually noted in your Works Cited list) and on which page you found it. Paraphrases and summaries should also have citations.

How to Cite Buddhist Scriptures?

For accurate citations of Buddhist sources, it is important to have a general understanding of a few key elements. There are three schools of Buddhism (Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana). Here, every school has its own tradition.

Each Buddhist school has a certain number of books, manuscripts, and formulas. Theravada formulas and written rituals are derived from the Pāli Canon. The Mahāyāna school is based on Chinese Buddhist tradition.

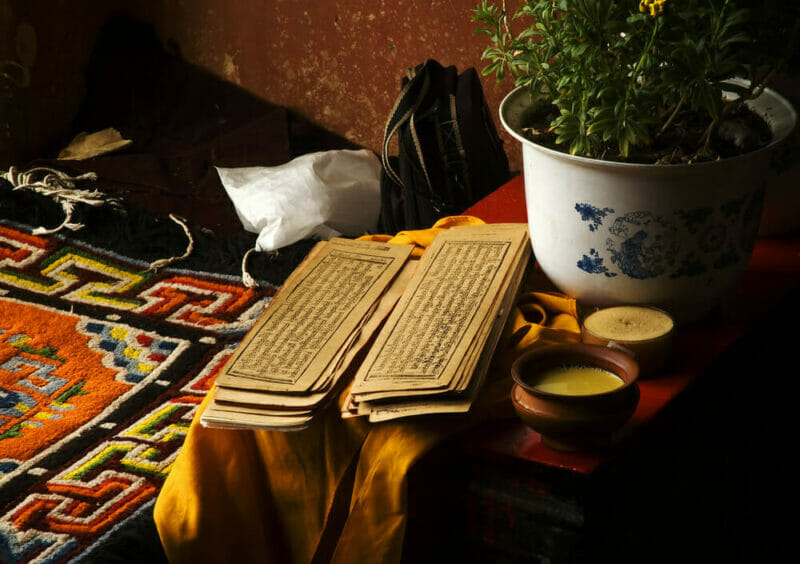

The Vajrayana branch, on the other hand, is mainly associated with Tibetan Buddhism. The Tibetan rituals are distinct and unchanged from those of other cultures.

In this light, we can see that the three branches of modern Buddhism are in direct line with the three traditions/disciplines of Pali, Chinese and Tibetan Buddhism.

Theravada is mostly practiced in Southeast Asian countries. Eastern Asia is the home of Buddhists who practice the Mahayana branch.

Tibetan rituals are practiced by followers of the Buddha in Central Asia. Tibetan rituals are primarily part of the Mahayana but are considered unique.

As I have already mentioned, for Theravda Buddhism, the Pāli canon serves as the foundation. Mahāyāna traditions follow iterations of the Chinese canon. And finally, the Tibetan canon is at the core of Tibetan Buddhism.

As the Pāli canon is considered to be the original version of the Tripitaka, we will first discuss how to quote from it.

Pāli canon suttas/sutras are usually divided into multiple chapters that can be quoted from.

Buddhist Scriptures: General Citation Format

In order to cite a scripture in an academic paper, you should include the name of the text followed by volume (V) and page number(s). The citation may also contain a date.

Quotes from the Pali Canon should follow a general rule. Digha or Majjhima Nikayas should be quoted with DN or MN added in front of the sutta and accompanied by a number.

You should also reference the section from which the sutta is quoted if it is taken from Saṃyutta Nikāya or Aṅguttara Nikāya.

When it’s in the fifth Samyutta, for example, put SN in front, then 5 followed by a period, and then the specific number of the Sutta in that section. The same is true for Aṅguttara Nikāya. Simply replace SN with AN.

Nowadays, many people refer to these numbers as “verse numbers,” so they would say “Anguttara Nikaya verse 15.”

Likewise, in the case of Khuddaka Nikaya, to quote a sutra, the name of the text is quoted, followed by the number under which the sutra appears in that collection.

In the examples below, we will see different ways and styles in which Nikayas are cited:

- “D.1,4”

- “DN 1”

- “DN 1, Brahmajala Sutta”

- “Digha Nikaya Sutta 1, Brahmajala Sutta: The Prime Net/The Perfect Net/The Supreme Net”

There are some collections that have sub-branches. Dharmapada (Dhammapada), for example, should be referenced by the chapter, then the sutta.

Mahayana Sutras should be cited only by their names. Generally, these suttas have multiple chapters that can be cited. Chinese canon suttas might be referenced with the Taisho number as well.

Additionally, it’s important to know whether it was originally written in Pali, Chinese, Sanskrit, Tibetan or another language so that you can find a corresponding English translation.

To cite these teachings in a blog post or paper requires citing sources where you found these teachings in order to show your readers how they can verify what you have shared with them.

Types of Buddhist Scripture

The majority of Buddhist scripture is known as “sutras” in Sanskrit or simple “sutta” in Pali, meaning “thread”. When there is the word “sutra’’ in the title, it means that it is a sermon of the Buddha or a major disciple. However, this is not verifiable as there are numerous other cases contrary to this belief.

Moreover, Sutras have different lengths; some are as long as a book while others are only a few lines. It is almost impossible to accurately mention the number and the quantity of sutras.

Likewise, not every sutra is a scripture. Additionally, there are commentaries in addition to sutras, rules for nuns and monks. Moreover, you will also find fables about the life of the Buddha, and other texts are also considered as “scripture”.

Theravada and Mahayana Canons

Around two millennia ago, Buddhism was divided into two schools – Theravada and Mahayana. Therefore, every Buddhist scripture is associated with one or the other.

Moreover, Theravadians challenge the authenticity of Mahayana scriptures. Contrarily, Mahayanan considers the majority of Theravadians as authentic. However, the friction remains between the two scriptures as to which is authentic.

Theravada Buddhist Scriptures

The collection of the Theravada scriptures is called the Pali Tripitaka or Pali Canon. Tipitaka is a Pali word meaning “three baskets”. Therefore, the Theravada is divided into three parts, where each part has its collection of works.

Following are the three baskets of sutras as per Theravada scriptures.

- Sutta-pitaka (basket of sutras)

- Vinaya-pitaka (basket of discipline)

- Abhidhamma-pitaka (basket of special teachings)

Mahayana Buddhist Scriptures

Mahayana scriptures are divided into two main types – the Tibetan Canon and Chinese Canon. Although, both sets of canons have mutual scriptures. Moreover, as the name suggests the Tibetan Canon is followed by Tibetan Buddhists. However, Chinese Canon is more authoritative as it is observed in the entire East Asia including China, Korea, Japan and Vietnam.

Moreover, there is a Sanskrit version of the Sutta-pitkas known as the Agamas. Although, historians doubt these writings as these were written in the 1st century BCE and 5th century BCE or even later.

Guide to Buddhist Scriptures

As we have seen previously, there are three main Buddhist scriptures preserved in three different languages. Let us now have a detailed look at these scriptures.

1. The Pāli Canon

Pāli is an ancient language, and most believe it is the same language that Buddha used to talk. It is unique in the sense that it is the only scripture preserved in its entirety. Further, it has three baskets and are discussed in coming lines.

Vinaya Pitkaka

A. Suttavibhaṇga – The rules of the Saṃgha or monastic code

i. Mahāvibhaṇga – 227 rules for monks

ii. Bhikkhunīvibhaṇga – 311 rules for nuns

B. Khandhaka – Matters related to the organization of the Saṃgha

i. Mahāvagga – Regulations for ordination, retreats, clothing, food, etc.

ii. Cullavagga – Procedural matters

C. The Parivāra – Appendix summarizing the rules

Sutta Pitaka

A. Dīgha Nikāya – 34 long discourses

B. Majjhima Nikāya – 154 medium length discourses

C. Saṃyutta Nikāya – 56 groups of discourses

D. Aṇguttara Nikāya – Discourses grouped by incremental lists of subjects

E. Khuddaka Nikāya – A collection of fifteen minor texts

i. Khuddakapāṭha – Short suttas

ii. Dhammapada – Popular collection of 423 verses on ethics

iii. Udāna – 80 solemn utterances of the Buddha

iv. Itivuttaka – 112 short suttas

v. Sutta-nipāta – 70 suttas in verse

vi. Vimānavatthu – Accounts of the heavenly rebirths of the virtuous

vii. Petavatthu – 51 poems about rebirth as a hungry ghost

viii. Theragāthā – Verses by 264 male Elders

ix. Therīgāthā – Verses by around 100 female Elders

x. Jātaka – 547 stories about the Buddha’s previous lives

xi. Niddesa – Commentary on portions of the Sutta-nipāta

xii. Paṭisambhidāmagga – Abhidharma-style analysis of points of doctrine

xiii. Apadāna – Verse stories on the present and former lives of monks and nuns

xiv. Buddhavaṃsa – An account of the 24 previous Buddhas

xv. Cariyāpiṭaka – Jātaka stories about the virtues of Bodhisattvas

Abhidhamma Pitaka

- Dhammasaṇganī – Psychological analysis of ethics

- Vibhaṇg – Analysis of various doctrinal categories

- Dhātukathā – Classification of points of doctrine

- Puggalapaññatti – Classification of human types

- Kathāvatthu – Doctrinal disputes among the sects

- Yamaka – Pairs of questions about categories of teachings

- Paṭṭhāna – Causation analyzed into 24 groups

2. The Chinese Canon

There are numerous Chinese Canons produced over the centuries, with the first being published in 983CE. Further, the modern edition is called the Taisho Shinshu Daizokyo that was published between 1924 and 1929 in Tokyo. This scripture contains 55 volumes, 2,184 texts having 45 supplementary volumes.

Here are details of the Chinese canon.

- Agama section: volumes 1–2, 151 texts. Equivalent to the first four Pāli Nikāyas and part of the fifth

- Story Section: volumes 3–4, 68 Jataka texts

- Prajna-paramita section: volumes 5–8, 42 texts of Perfection of Insight literature

- Saddharmapuṇḍarika section: volume 9, 16 texts relating to the Lotus Sutra

- Avataṃsaka section: Volume 9–10, 31 texts relating to the Avataṃsaka Sutra

- Ratnakuṭa section: Volumes 11–12, 64 early Mahayana text

- Mahaparinirvaṇa section: Volume 12, 23 texts concerning the Nirvaṇa Sutra

- Great Assembly section: Volume 13, 28 texts containing early sutras, starting with the Great Assembly Sutra

- Sutra-Collection Section: Volumes 14–17, 423 texts. Collection of miscellaneous sutras

- Tantra Section: Volumes 18–21, 572 texts. Contains Vajrayana Sutras and tantric materials

- Vinaya Section: Volumes 22–4, 86 texts. Contain the disciplinary texts of Hinayana schools and texts on Bodhisattva discipline

- Commentaries on Sutras: Volumes 24–6, 31 texts. Commentaries by Indian authors on the Agamas and Mahayana Sutras

- Abhidharma Section: Volumes 26–9, 28 texts. Translations of Sarvastivadin, Dharmaguptaka, and Sautrantika Abhidharma texts

- Madhyamaka Section: Volume 30, 15 texts. Texts on Madhyamaka thought

- Yogacara Section: Volumes 30–1, 49 texts. Texts on Yogacara thought

- Collection of Treatises: Volume 32, 65 texts. Miscellaneous works on logic

- Commentaries on the Sutras: Volumes 33–39. Commentaries by Chinese authors

- Commentaries on the Vinaya: Volume 40. Commentaries by Chinese authors

- Commentaries on the Sastras: Volumes 40–4. Commentaries by Chinese authors

- Chinese Sectarian Writings: Volumes 44–8

- History and Biography: Volumes 49–52, 95 texts

- Encyclopedias and Dictionaries: Volumes 53–4, 16 texts

- Non-Buddhist Doctrines: Volumes 54, 8 texts. Contains materials on Hinduism, Manichean, and Nestorian Christian writing

- Catalogs: Volume 55, 40 texts. Catalogs of the Chinese Canon

3. The Tibetan Canon

The Tibetan canon has majorly divided into two main parts – the Kanjur and the Tenjur.

I. Kanjur

It contains the words of Buddha having 98 volumes as mentioned by Narthang edition.

A. Vinaya – 13 Volumes

B. Prajna-paramita – 21 volumes

C. Avatamsaka – 6 volumes

D. Ratnakuta – 6 volumes

E. Sutra – 30 volumes

F. Tantra – 22 volumes

II. Tenjur

It contains commentaries having 224 (3,626 texts) volumes as per the Peking edition, the details are mentioned below.

A. Stotras – 1 volume (64 texts)

B. Commentaries on the Tantras – 86 volumes (3,055 texts)

C. Commentaries on the Sutras – 137 volumes (567 texts)

- Prajna-paramita Commentaries (16 volumes)

- Madhyamaka Treatises (17 volumes)

- Yogacara Treatises (29 volumes)

- Abhidharma, (8 volumes)

- Miscellaneous Texts (4 volumes)

- Vinaya Commentaries (16 volumes)

- Tales and Dramas (4 volumes)

- Technical Treatises (43 volumes)

Video: Buddhist Scriptures for Beginners

Frequently Asked Questions

What are Buddhist scriptures written in?

Buddhist scriptures are written in an ancient Indian language called the Pali. This language is very close to what Buddha has spoken himself.

How do you cite Buddha?

You can use BKS as a guide for numbering, as references are related to samyutta and sutta numbers. For instance, SN 57.12 is sutta number 12 within the samyutta number 57.

What are the scriptures for Buddhists?

Here are three main types of scriptures for Buddha.

- Pali Canon

- Chinese Canon

- Tibetan Canon

What is the word for Buddhist scripture?

Early Buddhist scripture is part of the “sutta” or “sutra” genre. These scriptures are attributed to Buddha or his close disciples.

Parting Words

The Buddhist scriptures contain a wealth of wisdom and insight, and if you wish to use them in your own work, it is important to ensure that they are properly cited in order to give credit where it is due.

The Buddhist scriptures are a diverse collection of texts that were composed over many centuries in various languages, and as a result, they do not adhere to a single standard citation format.

Scholars often rely on individual texts that have been properly published in a language that follows established bibliographic conventions.

It is important to keep in mind that there are many different translations of Buddhist scripture available, and not all of them may be accurate in every context.

It is always advisable to double-check any information before using it as part of an argument or as supporting evidence in an academic paper.